Automating myself out of a role

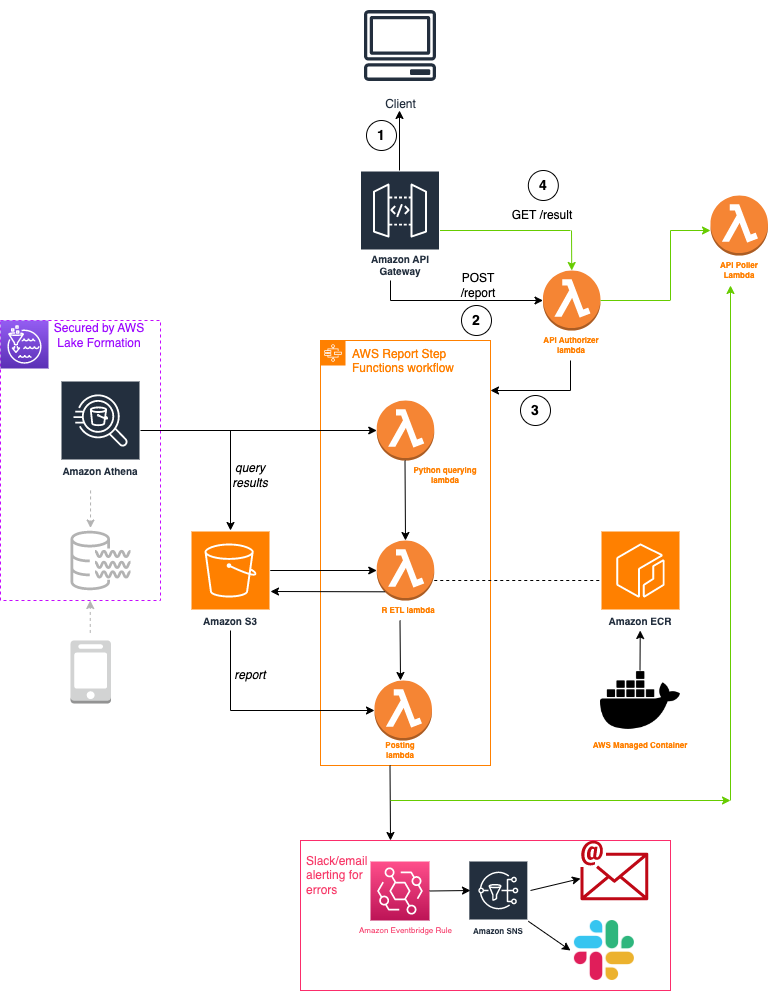

This is what I’ve designed and built recently to automate myself out of a process that we used to do very manually at chnnl:

There’s a lot going on above, but what you see is a reporting workflow we have tried to automate for 2.5 years. The motivation to automate can be summarised by the ff:

- the report is a key service offering of chnnl

- the data and insights chnnl wanted out of it increasingly matured and stabilised over time

- the report took analysts anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours to produce and validate which wasn’t a scaleable duration

- aspects of the report generation process were repetitive and deterministic and could be codified

At the tail end of this automation, I can proudly report some technical and business learnings from having embarked and led this full-stack project. While i’m planning to write separate posts breaking down all of my learnings, for now, I’ll briefly talk about the architecture I’ve adopted for the project, what it does, and why I made the choice to go with certain components I went with.

Read on if you are wanting a very high level overview of what cloud microservices go into a workflow like this, or are interested in general cloud architecture work like me.

This post is inspired by AWS’ This Is My Architecture series, where architects or leaders from different companies speak about architectural decisions they’ve made on AWS that power their core products and business. I highly recommend browsing through the series when you research suitable architectures for your own AWS project.

What’s this architecture for?

The architecture above is for an automated reporting system that outputs summarised wellbeing data for chnnl clients in a multi-page excel sheet. The main users of the system are chnnl’s customer care team, who produce reports from this and use them downstream for conversations with clients on workplace wellbeing. A customer care manager at chnnl, the user of the reporting system, would produce a report per client per recurring period of time (i.e. a report for client A every 2 weeks, client B every month, etc), and therefore the reporting date range and client name are parameters to the system. Given these parameters, the system fetches data from chnnl’s secured data lake, applies transformations and aggregations on the data, writes the results to an excel file, and sends the result back to the user in less than a minute. The user interacts with a web form and sees the result displayed on this form.

Pre-Automation

Before this automation, an analyst would take various manual steps to produce the report. The analyst would query raw report data with SQL, download the data to their local machine, fire up an interactive R session and run R scripts that transform and aggregate the data, then copy the transformed results onto an excel file–very manual, unscaleable and error-prone. This was done in the early days of the report as the information contained in the report changed a lot as per user requirements, so the analyst had to write functions to accommodate. There were few clients opting into the report service then as well, so doing it all manually wasn’t a major timesink yet.

Need to automate

As chnnl’s clientele grew and the requirements reached a stable point, automation increasingly made sense. We started to think about architectures to automate this system and the only technical considerations were:

- the only manual point should be the entering of the report parameters. Everything else has to be automated.

- we had to keep the data transformations in R, the language they were originally written in for stability. Rewriting to python for example would take time

- every component is provisioned with Infrastructure as Code (IaC)

Architecture

First, I’ll walk through what the flow involves.

- A user interacts with a web form, inputting parameters that are needed to produce a report

- When the user submits the form, these parameters are posted to an API route

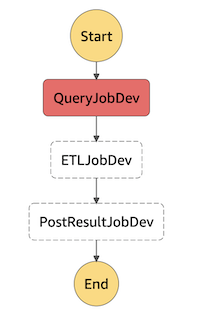

POST /report. - This route triggers an AWS Step Function workflow, which causes the report to be produced. This flow chains various AWS lambda functions doing various tasks: 1.) querying AWS Athena for raw data 2.) performing ETL on this data and producing the final excel report and 3.) outputting an authenticated S3 URL to download this report.

- There is another API route that gets invoked every few seconds by the form (

GET /result) which polls and returns the status of the reporting workflow. Once the workflow completes, the authenticated URL is made available to the form. Otherwise, a pending status is displayed, as are errors, which are additionally broadcasted on a slack channel monitored by chnnl devs for easier visibility and debugging.

Choosing the architecture

Now I’ll talk through the different components I used to build the flow and briefly explain why I chose them.

Lambda

Lambda functions allow you to run code without worrying about provisioning servers. Any code involving business logic were transferred to lambdas in this project. In the report generation flow, I had three lambdas: 1.) a lambda querying input data from chnnl’s data lake with SQL 2.) a lambda transforming and aggregating data and creating the report 3.) a lambda creating an authenticated, pre-signed URL of the report for download later. I also had lambdas for authenticating HTTP requests to my report API, as well as polling the status of the reporting workflow. Lambdas made sense for running functions as they are severless and low-cost. They supported the creation of custom language runtimes like the one I made to accommodate my ETL scripts in R, and for python runtimes, had boto3, the SDK for AWS natively installed. An alternative to lambda obviously is running an always-on server that hosted my reporting code, which was unnecessary because report production is on-demand.

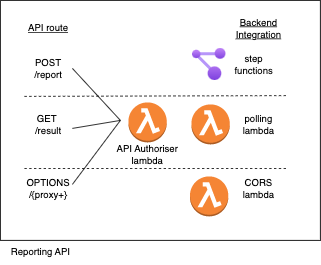

API Gateway

As opposed to running the report on schedule, an API was needed to produce the report on-demand. The parameters to the report had to be passed to the API. I created two routes on a single HTTP API in API Gateway, one for starting report production (POST /report), and the other for polling its status (GET /result). This made sense vs creating two separate APIs, as both related to the same task – the reporting task. I used an HTTP as opposed to REST or websocket API as I wanted something low cost, that I didnt need to configure as much, and my use case didnt involve duplex communication. I also had to create a third route on the same API to handle CORS requests from browsers, which were sent due to the presence of Bearer tokens on my API request headers for added security. All routes had an authorization lambda that authorised the Bearer token and an AWS service integration that carries out the backend task attached to the API route.

Step Function Workflow

Step Functions (SF) were used in this context as a workflow orchestration tool, to chain together the three lambdas producing the report. The alternative to SF is to have one lambda run the two other lambdas, but this makes code non-modular. SF allows us to pass data from one lambda to another and debug precisely where in the reporting workflow did errors originate. An open source equivalent of SF would be airflow or prefect, for example, which shows processes in a DAG like SF does. Our usage of SF here is very simple–just chaining lambdas together–however, SF allows for conditional workflows, retrying processes when they fail, and many other processes. SF also conveniently integrates directly with API gateway, so that the POST /report endpoint passes data directly to the SF workflow, as well as AWS EventBridge, which can listen to any errors SF generates.

Others

- S3: used as the storage mechanism for dumping intermediate and final report data. The final report was downloadable via a pre-signed S3 URL of the final report file. I’ve used one bucket to hold everything related to the report, with different folder structures to house different artefacts. I’ve also enabled bucket tiering to save costs, such that objects in the bucket that are unused for >3 months are transferred to a cheaper bucket used for archiving.

- AWS ECR: used to host the docker container for running the ETL scripts written in R. The R lambda I’ve created runs this docker container every time it’s invoked. I’ll detail the R lambda creation in a separate post, but I’ve used an Amazon Managed Image (Linux, al2) as my base to build the container.

- Cloudwatch Logs: used extensively to debug during the development process. I’ve manually enabled my APIs to stream to logs while developing so I can debug what aspects of the API errors out (i.e. is it the step function workflow, the API authorization process, a client-side error, etc?). This will turn off in production to save costs. I’ve kept logs on in services that have them turned on by default (i.e. Lambda).

- AWS EventBridge: used to create an event rule, a pattern that detects when the step function workflow errors out/gets cancelled. If this pattern is met, event bridge broadcasts a message to an event listener. I used this workflow to broadcast production errors of the reporting system to a slack channel, as detailed below.

- Cloudformation: used to build and deploy the entire architecture with code (infrastructure as code). The architecture was created as a cloudformation stack, which can be synthesised, deployed and destroyed with simple CLI commands. Instead of using cloudformation templates, I used AWS CDK as this was a pre-existing devops choice chnnl adopted, which I’m happy with, as CDK is available in typescript and python. This made provisioning infrastructure easier as I didn’t have to learn another language like i would using cloudformation/ARM templates for deployment for example.

- Athena: I didn’t create this, but this was available as a way to interactively access our data-lake via SQL commands. I built the reporting system to run SQL code to query Athena automatically using saved Athena queries. One thing to note is that Athena is built as a UI/IDE to run SQL commands interactively for analysts, and therefore might be costly to use at scale. When this happens, one would likely forego Athena and run queries against a data warehouse for eg.

Monitoring with SNS, Event Bridge, Cloudtrail

When running microservices, monitoring crucial potential failure points is necessary. As mentioned before, some services like lambda have log streaming available by default. Not all of those logs will be useful though, and those logs are in the AWS server and not in a place we can easily access or view. For this reporting system, I’ve tried to account for errors client-side by form validation mechanisms in the web form I’ve created. Because of the tight timeline of the project, I reasoned that I can’t enumerate all possible errors that may escape that client-side validation, or may originate server side, so it’s better for me to have a catch-all mechanism that broadcasts errors to a place I can see/access. I could then develop better error handling mechanisms after seeing what errors come up time and again.

This catch-all mechanism was developed with a combination of AWS Event Bridge (EB) and AWS Simple Notification Service (SNS). I created various rules in EB that detect a FAIL, CANCEL, ABORT status for any step of my step function reporting workflow, and a rule detecting the absence of a report file in S3 after the workflow is run, which can indicate failure for any number of reasons not captured by the previous rule. These event failure rules in EB were tied to event listeners in SNS, which, in response to a broadcasted event from EB, send the details of the event to a development and production slack thread in chnnl. This allows monitoring of failures in dev and prod as they happen, which is handy for debugging on the spot.

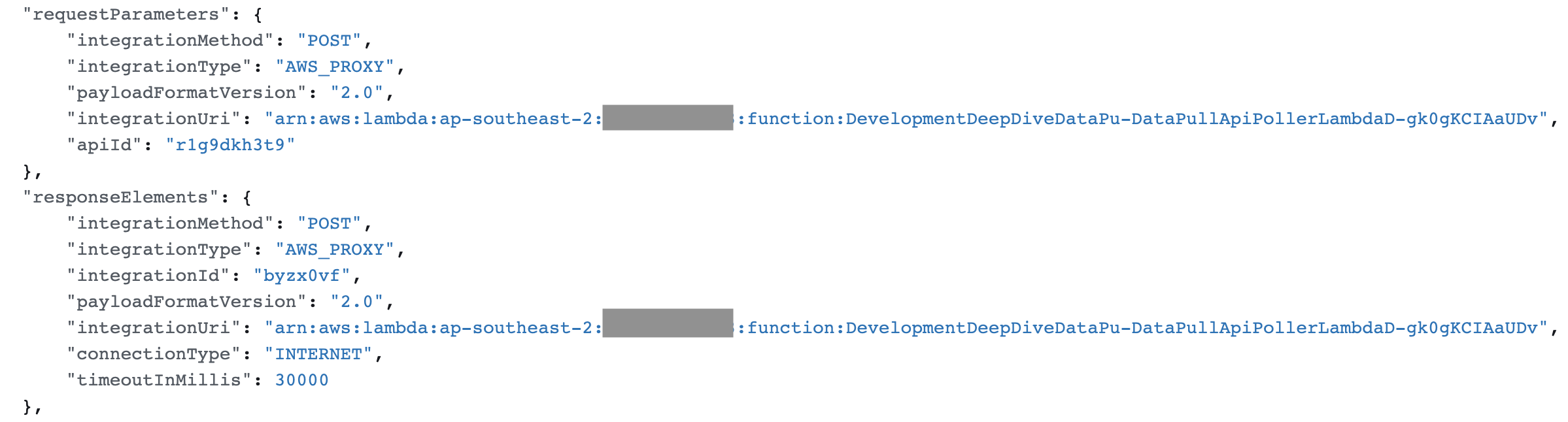

Finally, I used AWS Cloudtrail extensively during development to translate how the creation of different microservices in the console can be reproduced and codified in AWS CDK. When developing any AWS service, I often quickly PoC the service on the console to give me an idea of how to create and test it, then codify the service with AWS CDK later when it is tested and working.

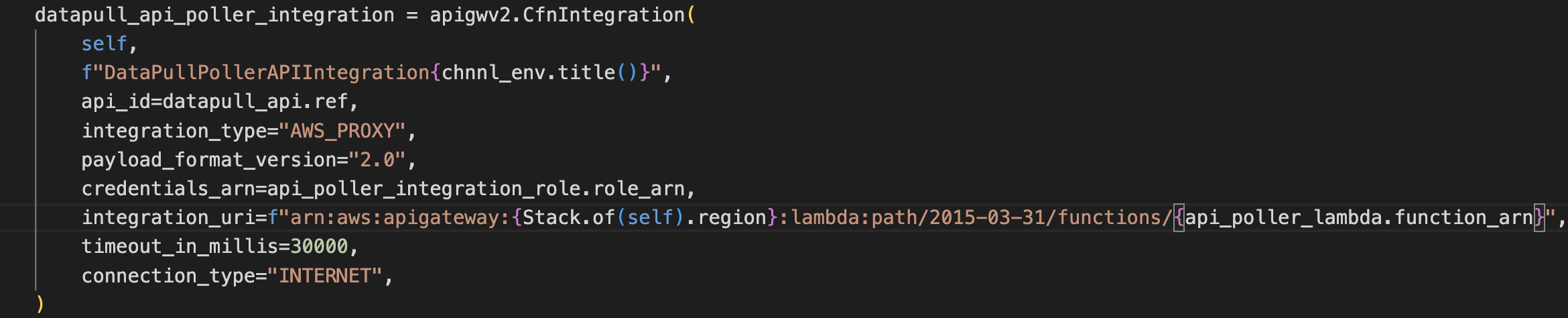

An example is the creation of an API integration on the console and CDK. To preserve all of the configurations that are baked in by default when creating that service in the console, I often inspect Cloudtrail logs generated during the console creation event. I then make sure that all the necessary parameters are copied over to CDK, because otherwise the integration might not work as well as it does on the console (Fig 3 below). Cloudtrail contains information about all events executed in an AWS plan.

Conclusion

This post summarises architectural components and choices I made to design a reporting system that was previously very manually done. I’d love to extend this post by showing you costing, or how much it takes to run one workflow end-to-end in AWS. I’d also love to share some research I did on open source equivalents of the above workflow, as well as thoughts on how to scale it up. Those will be in a future post so stay tuned!

I actually haven’t automated myself fully from chnnl, just from the reporting I used to do very manually. Hours of report production are now delegated to a system in the cloud, freeing me up to focus on other full-stack engineering and machine learning projects that may provide value to the business. As an engineer I’ll definitely view every project now as amenable to automation, and carefully design my architecture and craft my code to make it flexible for this in the future.